An empirical measurement of Technical Debt

What is technical debt, really?

We had an interesting discussion about the nature of our technical debt and what we should be doing to solve it and arrived at the following conclusions:

- The most important debt to resolve is the debt with the highest interest

- The highest interest is a combination of how often the code is used and how bad the code is

- Its not just code making up technical debt

Wikipedia roughly agrees with us:

The implied cost of additional rework caused by choosing an easy solution now instead of using a better approach that would take longer.

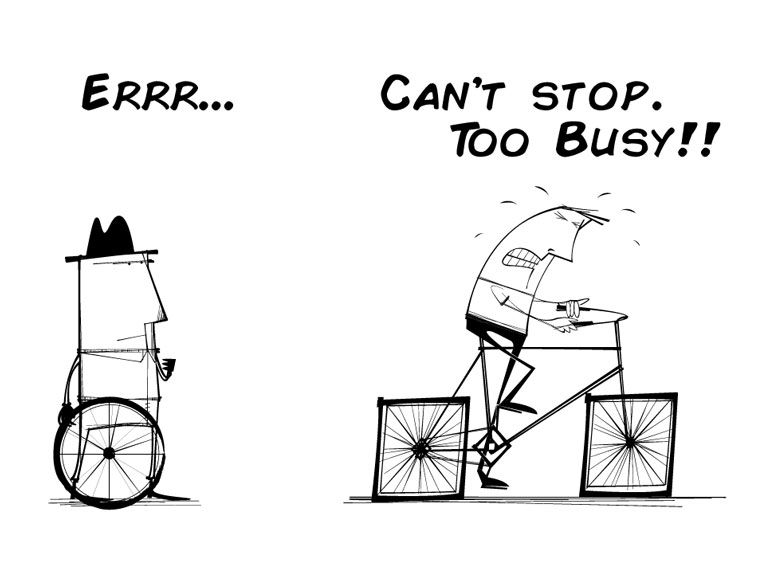

So we decided that a relative measure of how much a piece of code actually slows us down was needed.

How then? Commit frequency.

We needed a way to quantify how much people are being slowed down by a given piece of code.

Commit frequency gives us a nice way to figure this out:

- We assume that committing more frequently is preferable (…and we say it is, and encourage people to do it…)

- so the only reason for not committing more frequently is that you can’t

- and the reason you can’t we define to be our technical debt because

- if we re-factored, re-architected or otherwise improved then you could.

Of course, this ignores other reasons for not committing like “went to get a coffee”, “got interrupted” or “cat fell onto keyboard” - but we’re assuming that all of this comes out in the wash.

Stats!

First thing to do is find out how long commits “usually” take. So we pulled out the commit logs from all of the repos and plotted the time between commits.

It turns out that you can fit a log-normal (...ish, its ln(x)2) curve to this, which means we can pull this into normal distribution and test some ideas.

I'm impressed at how well this fits...

There is a fair bit of detail omitted here: we also normalised across authors and put some work in to remove holidays, weekends and such.

Sidebar: A log-normal is form from a product of independent variables, which possibly means that a longer commit time is the result of one action in the dev-test loop taking longer which multiplies across the other actions? Makes sense I guess?

Comparing distributions: Z-Scores

Now we can figure out which files take longer to work on by assuming that all commits with a given file in also make up a normal distribution - which we can compare to our standard distribution under the same normalisation using a z-score:

def zscore(commits):

"Z-Score per-file for all files in commits"

perpath = defaultdict(list)

for commit in commits:

for path in commit.paths:

perpath[path].append(commit.interval)

return {path : sum(perpath[path]) / math.sqrt(len(perpath[path]))}

Given these, we can sort to find the worst z-scores and plot these back on the normalised graph.

This nicely shows that “CloudyStuff” usually takes a lot longer between commits, roughly 3-6 times as long as it usually takes. So that gives us a measure against the normal for an individual file and a list of the worst offenders.

In our specific case, CloudStuff didn’t have a very good mock backend, so many changes to the

CloudyStuff require uploading and interacting with a cloudy thing. This is obviously going to be

slower than a dev-test loop on a local machine, followed by a final test on the cloud.

The other big offender was due to on-boarding a new piece of code which had end-to-end tests, but no integration tests or unit tests. In this case we made the loop require writing characterisation tests which necessarily slowed it down.

Adding it all up

So we can now pull out a graph of technical debt, or rather, the interest currently being paid on technical debt - which we are arguing is more important.

We can add all of this debt up by saying that “interest on debt” is:

The amount of time spent on commits above α standard deviations that contain a file which is α standard deviations away from usual.

In python the code looks like this:

def debt(commits, deviation=1):

"Total debt for this series of commits"

scores = zscore(commits)

debt = 0

for commit in commits:

for path in commits.paths:

if scores[path] > deviation:

debt += commit.duration -

inverse(0) -

inverse(deviation)

return debt * 100.0 / sum(c.duration for c in commits)

We use inverse to apply the reverse of the log-normal transform so that we’re looking at a percentage of “real” time:

Its a bit of a jumpy graph, but that is because we’ve not actively tried any measures (yet). There is a theory that some of the sudden falls represent new pieces of work (and so are clean from debt) and the rises (may) correspond with legacy product release cycles.

Does this make sense?

What about things that don’t go in version control?

First off… everything should be in version control! Easy. Of course, there are always actions that aren’t - but these are either independent of the current commit (so won’t affect the data when taken in volume) or do affect the current commit - in which case they are technical debt.

What if some people take more care than others?

We normalised on a per-author basis to try and make our data about the code and process, rather than the individual.

Interest is only paid when code is currently active, so a drop in interest may just mean the current active code is better

This is very true… and is definitely an issue. Inactive code with high technical debt represents risk but isn’t actually holding things back… yet. This is where secondary metrics (complexity, coverage and linting) can help - particularly if a link to the empirical measure of debt can be found. …watch this space.